MACON – Mercer University associate professor of biology Dr. Craig Byron, along with an international team of researchers, recently released findings that reveal an early human ancestor did not have the jaw and tooth structure necessary to exist on a steady diet of hard foods, as previous findings had suggested.

Research published in 2012 earned international attention for suggesting that Australopithecus sediba – a diminutive pre-human species that lived about two million years ago in southern Africa – had subsisted on a diverse woodland diet, including hard foods mixed in with tree bark, fruit, leaves and other plant products.

“Most australopiths are known for jaw, teeth and facial anatomy that allowed them to process foods difficult to chew or crack open. It is accepted that the architecture of their chewing system enables efficient biting and produces very high forces,” said Dr. Byron, who also serves as associate chair of Mercer's Biology Department.

“Australopithecus sediba is thought by some researchers to lie near the ancestry of Homo, the genus to which our species belongs. The results of this study suggest that A. sediba had an important limitation on its ability to bite as powerfully as possible; if it had bitten as hard as possible on its molar teeth using the full force of its chewing muscles on both sides of the jaw, it would have dislocated its TMJ (temporomandibular joint).”

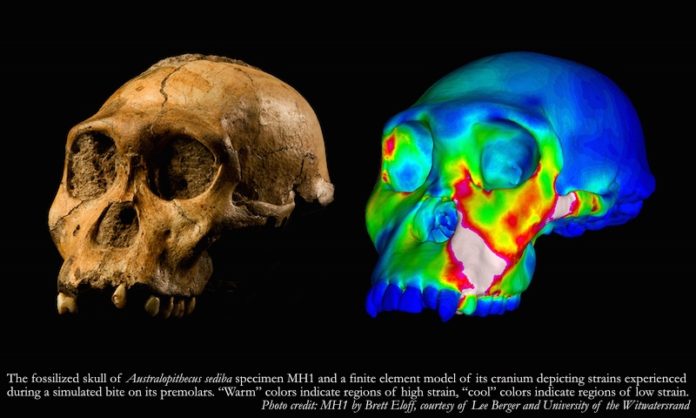

The study, published in the February 2016 issue of the journal Nature Communications, describes biomechanical testing of a computer-based model of an Australopithecus sediba skull. The model is based on a fossil skull recovered in 2008 from Malapa, a cave near Johannesburg, South Africa. The biomechanical methods (finite element analysis, or FEA) used in the study are similar to those used by engineers to test whether planes, cars, machine parts or other mechanical devices are strong enough to avoid breaking during use.

Australopiths are present in the fossil record four million years ago, and although they have some human traits, such as the ability to walk upright on two legs, most of them lack other characteristically human features like a large brain, flat faces with small jaws and teeth and advanced tool use.

Humans in the genus Homo are almost certainly descended from an australopith ancestor, and A. sediba is a candidate to be either that ancestor or something similar to it.

The new study does not directly address whether Australopithecus sediba is indeed a close evolutionary relative of early Homo, but it does provide further evidence that dietary changes were shaping the evolutionary paths of early humans.

“Like A. sediba, modern humans also have this limitation on biting forcefully, and we suspect that early Homo had it as well, yet the other australopiths that we have examined are not nearly as limited in this regard,” Dr. Byron said. “This means that whereas some australopith populations were evolving adaptations to maximize their ability to bite powerfully, others, including A. sediba, were evolving in the opposite direction.

“One of these populations likely gave rise to our genus Homo. Thus, a possible key to the origin of our genus rests in understanding how ecological change may have disrupted typical australopith feeding behaviors. A shifting dietary focus is likely to have played a key role in the origin of Homo.”

Some of the researchers who described A. sediba are also authors on the biomechanical study, including Dr. Lee Berger and Dr. Kristian Carlson of the University of the Witwatersrand and Dr. Darryl de Ruiter of Texas A&M University.

Other co-authors include Dr. Justin A. Ledogar, University of New England, Australia; Dr. David Strait, Washington University, St. Louis; Dr. Stefano Benazzi, University of Bologna and Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology; Dr. Gerhard W. Weber, University of Vienna; Dr. Mark A. Spencer, South Mountain Community College; Dr. Keely B. Carlson, Texas A&M University; Dr. Kieran P. McNulty, University of Minnesota; Dr. Paul C. Dechow, Dr. Qian Wang and Dr. Leslie C. Pryor, Baylor College of Dentistry at Texas A&M University; Dr. Ian R. Grosse, University of Massachusetts, Amherst; Dr. Callum F. Ross, University of Chicago; Dr. Brian G. Richmond, American Museum of Natural History; Dr. Barth W. Wright, Kansas City University of Medicine and Biosciences; Dr. Kelli Tamvada, The Sage Colleges and formerly, the University at Albany; and Dr. Michael A. Berthaume, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.