The Lost Colony of Roanoke is one of America's greatest mysteries and, thanks in part to the work of a Mercer professor, that mystery may be solved sooner rather than later.

Dr. Eric Klingelhofer, professor and chair of the Department of History, is vice president of research for the First Colony Foundation, a non-profit organization founded in 2004 to gather evidence of Sir Walter Raleigh's attempts to establish English colonies on Roanoke Island, N.C., in the 1580s under a charter from Queen Elizabeth I.

Soon after earning his Ph.D. in medieval history from The Johns Hopkins University and joining the Mercer faculty, Dr. Klingelhofer was contacted by a former boss at Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia about beginning excavations at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site on Roanoke Island. Those excavations, from 1990-1992, yielded surprising results. The site researchers had been examining was not a settlement; rather, it was an earthwork structure where Elizabethan scientists — including Raleigh's top scientist Thomas Harriot — examined the raw materials of North America.

But where was the settlement?

Dr. Klingelhofer and his colleagues later determined that evidence for it must have been masked by landscaping or hidden beneath natural areas of woods and dunes in the national park established there in 1941. This prompted the formation of the First Colony Foundation and, over the past 10 years, work has been done off and on at the site, including three trips by Dr. Klingelhofer and Mercer students.

This latest discovery, which gained international attention because of an online article by National Geographic on Dec. 6, 2013, did not come from the ground, however. It came from inside the walls of the British Museum. A map, drawn in 1585 by John White, an artist and governor of the colony, led archaeologists to a site in southern North Carolina where explorers met with Indians and drew pictures of those Indians and settlements in the area.

After comparing the site to the map and noticing some inconsistencies, including a patch on the map itself, members of the First Colony Foundation contacted the museum for more information. There turned out to be not only one, but two patches on the original map, and no one had ever looked underneath them. The other patch, on top of a location in northern North Carolina on the Albemarle Sound, covered up an illustration of what appeared to be a fort.

Following further research by Dr. Klingelhofer, editor of the book First Forts: Essays on the Archaeology of Proto-colonial Fortifications, and his colleagues, the First Colony Foundation held a press conference in 2012 at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to announce the discovery of apparent interest by Elizabethan authorities in an area quite far from Roanoke Island.

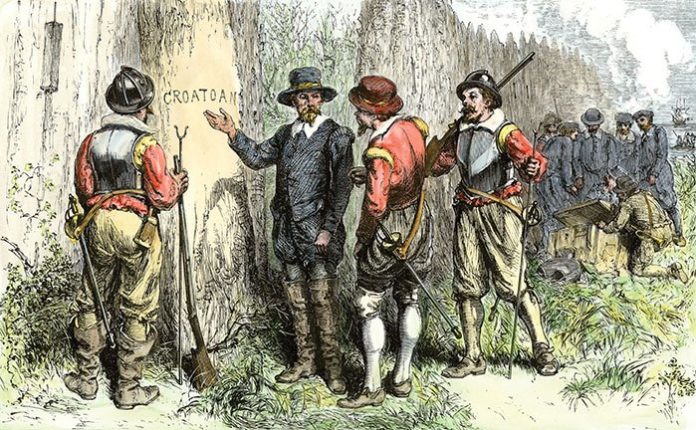

A popular theory had existed that the colonists abandoned the island and traveled some 50 miles south to Hatteras Island, then known as Croatoan Island. That would explain the only two clues found by the search party sent by Raleigh in 1590: the word “Croatoan” carved into a post and “Cro” carved into a tree. However, it now appeared that the colonists did travel 50 miles, but in a different direction, west via Albemarle Sound toward the mouth of the Chowan River.

“That is where we've been doing our most recent excavations, and we believe we have locked in on the site that is marked on the map, adjacent to an Indian site that is also marked,” said Dr. Klingelhofer.

The First Colony Foundation employed magnetometers and ground-penetrating radar (GPR) to investigate this newly identified area that might help explain the fate of the lost colonists. The findings indicated the possibility of one or more structures, formerly made of wood, as well as numerous prehistoric features. However, these structures could be left from later colonial sites that populated the area through the 1700s.

Excavation won't take place immediately. In the interim, Dr. Klingelhofer recently took students to St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands over spring break to resume work at a small settlement discovered by previous Mercer teams. This latest team determined that the site dated to the mid- to late-17th century French occupation of the island, and is possibly the earliest plantation discovered in the Virgin Isles. The project had been on hold for two years while Dr. Klingelhofer focused on the First Colony Foundation projects.

“We dug three small test pits, scoured the beach for cultural artifacts and remapped some of the original excavations on the island,” said Joshua Whitfield, a senior from Jefferson who traveled with the latest group to go to Roanoke during the fall semester of 2012.

All of the most recent work, which resulted in the National Geographic article, was done only by professionals, without the help of student volunteers. The publicity that followed isn't something new for the professor who has long been researching a story that captivates so many.

“Every few years, there is a new documentary on Sir Walter Raleigh's Lost Colony, so every five to 10 years, I'm famous,” said Dr. Klingelhofer, who has been featured in media outlets such as USA Today, NBC and the BBC.

He tends to believe some of the same theories about the fate of the colonists that are prevalent among other archaeologists and historians. When White returned to Roanoke Island on Aug. 18, 1590, none of the 90 men, 17 women and 11 children — whom he had left to seek help almost three years earlier — remained. There was no sign of a struggle. Likely, they split up because of the difficulty of surviving in the wild. Possibly, a small group traveled out to the shores of the islands to try to flag down passing ships. Some could have succumbed to disease. Others could have intermarried into the Indian tribes of eastern North Carolina. These tribes were some of the most affected by expansion, disease and war, so they were extremely difficult to document.

And after a generation passed, by the 1620s, no mention can be found of any of these colonists.

“Their people never came back. They never rescued them. It must have been like being stranded on Mars,” said Dr. Klingelhofer. “We fully believe that our work is worth it, if nothing else but for the sacrifice and hardship that these first English-speaking Americans went through.”

To view a full gallery of images from one of the digs performed by Dr. Klingelhofer and his students, click here.

Illustration by North Wind Picture Archives/Alamy